Students of Color Face Steep School Funding Gaps

“In the county [schools], EVERYTHING is better! Over here, we live in the ghetto; we’re not getting much. So getting school funding based on property taxes isn’t gonna do anything for the kids. And it’s horrible because schools like this have a lot of kids with a lot of potential. Just because we’re born in the city doesn’t mean that we’re going to be failures. But they don’t want to put in that extra effort at providing what we need for an education — like calculators and computers and stuff like that.”

These are the words from a Black 10th-grader from a large, metropolitan public school system. Apparently, even a high school student can be savvy enough to understand school funding gaps.

Today, Ed Trust releases an updated school funding gaps analysis that joins a rich body of work showing how students from low-income families are not getting their fair share of school funding. But Funding Gaps 2018 goes a step further by building upon existing evidence that there are also significant funding disparities for students of color.

In fact, when we looked at state and local funding for districts serving the largest concentrations of historically underserved students — those who are Black, Latino, and Native American — we found funding gaps to be nearly twice as large as those based on poverty.

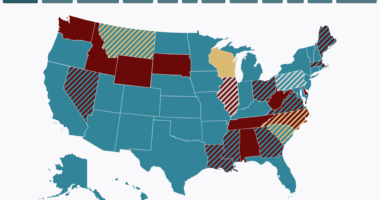

The report reveals that the highest poverty districts in the U.S. receive about $1,000 less per student than the lowest poverty districts, while districts serving the most students of color receive roughly $1,800 less per student than those serving the fewest. And this national pattern of inequity is replicated within 14 states — states that educate 40 percent of our Black, Latino, and Native American students — where the districts serving the most students of color receive at least 5 percent less funding per pupil than the districts serving the fewest.

Of course, there are historical, systemic reasons for this. On average, 36 percent of total school funding comes from local property taxes. But discriminatory lending and zoning practices have suppressed local property wealth in communities of color — many of which are still recovering from the Great Recession — and have contributed to the devastatingly large racial wealth gap. When local property taxes form the foundation of school funding systems, it compounds the impact of injustices inflicted on communities of color outside the school by systematically underfunding their children inside of school.

But these inequities are not inevitable. Instead of simply allowing this cycle to continue, some states are working to counteract funding inequity across districts. Our analysis reveals 14 states that have a progressive funding pattern, where districts serving the most students of color receive at least 5 percent more funding than districts serving the fewest.

As we continue to advocate to eliminate inequities in the American education system, it’s important to note that students of color sometimes experience inequities that are distinct from those faced by students from low-income families. While efforts to tackle inequitable access to resources for students from low-income backgrounds are important, they should not replace measures to ensure equity for students of color. This analysis is yet another data point showing that poverty is not a proxy for race or ethnicity.

In the meantime, students of color, like the Black 10th-grader quoted earlier, feel the brunt of this inaction. As social psychologist Michelle Fine has noted, “Poor and working-class youth of color are reading these conditions of their schools as evidence of their social disposability.” In an America that prides itself on equality and opportunity, no child should feel disposable. It’s time we worked toward a future where every student gets her fair share of school funding, regardless of her race, ethnicity or zip code.